First of all we investigated the Pepperell connection. This

search took us a long way from Froyle and back in time over two hundred years

to before the American Declaration of Independence. The first Sir William Pepperrell was born in 1696 at Kittery Point, Maine (then part of Massachusetts). A wealthy merchant, landowner, and businessman, he became a colonel in the colonial militia, was a delegate to the Massachusetts General Court and a member of the governor’s council, and was appointed chief justice in 1730. In 1745 he commanded the land forces that, with a British fleet under Sir Peter Warren, captured the French fortress of Louisburg, on Cape Breton, Canada and became known as ‘The Hero of Louisburg’. In recognition of this service, he was the first Native American to be created baronet in 1746 and briefly governed Massachusetts between 1756 and 1757. He died in 1759.

These were tempestuous years as the colonies in America struggled to break free of British rule - a struggle that divided the people into those who wanted liberty from the king and the loyalists who supported the status quo. In 1774 he was chosen as a member of the governor's council, but when this council was reorganised under the act of Parliament, he fell into disgrace because of his loyalty to the king. On November 16th 1774, the people of his own county passed a resolution in which he was declared to have “forfeited the confidence and friendship of all true friends of American liberty, and ought to be detested by all good men.” Thus denounced, the baronet retired to Boston, and, in 1775, sailed for England. His beautiful lady, one is saddened to learn, died of smallpox ere the vessel had been many days out, and was buried at Halifax. However, in “The Elegant Royalls of Colonial New England”, her obituary in the Boston News Letter of October 19th 1775 states that “Last Sunday morning (October 14th), after a few days illness, departed this life in the 28th year of her age, the Lady of the Honourable Sir William Pepperrell, Baronet....... Her remains were very respectfully interred last Thursday evening”. The statement in the previous paragraph from “The Romance of Old New England Rooftrees” stating that she died at sea is, obviously, incorrect. In England, Sir William was allowed £500 per annum by the British government, and was treated with much deference. He was the good friend of all refugees from America, and entertained hospitably at his pleasant home. His private life was irreproachable, and he died in Portman Square, London, in December, 1816, at the age of seventy. His vast possessions and landed estate in Maine were confiscated, except for the widow's dower enjoyed by Lady Mary and her daughter, Mrs. Sparhawk. On July 4th 1776 Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence and everything changed.

|

|||

|

|

|||

| Text extracts from The Romance of Old New England Rooftrees by Mary Caroline Crawford Eighth Impression, March, 1908 Original painting is the property of Harvard Law School, Cambridge MA US |

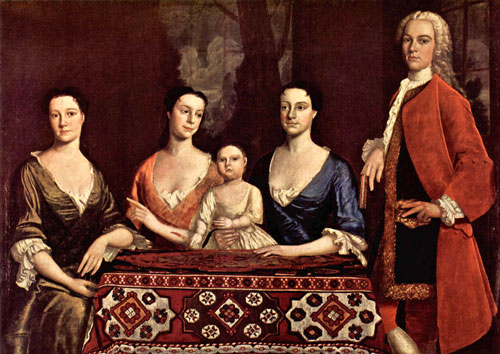

His father-in-law, Isaac Royall

(pictured left with his family in 1741), though he acted not unlike his son-in-law, Sir William, has, because of his vacillation, far less of our respect than the younger man in the matter of his refusal to cast in his lot with that of the Revolution. In 1778 he was publicly proscribed and formally banished from Massachusetts. He thereupon took up his abode in Kensington, Middlesex, and from this place, in 1789, he begged earnestly to be allowed to return ‘home’ to Medford, declaring he was “ever a good friend of the Province”, and expressing the wish to marry again in his own country, “where, having already had one good wife, he was in hopes to get another, and in some degree repair his loss.” His prayer was, however, refused, and he died of smallpox in England in October 1781. By his will, Harvard College was given a tract of land in Worcester County, for the foundation of a professorship, which still bears his name. But, what is the connection between these two famous names from American history and Froyle?

His father-in-law, Isaac Royall

(pictured left with his family in 1741), though he acted not unlike his son-in-law, Sir William, has, because of his vacillation, far less of our respect than the younger man in the matter of his refusal to cast in his lot with that of the Revolution. In 1778 he was publicly proscribed and formally banished from Massachusetts. He thereupon took up his abode in Kensington, Middlesex, and from this place, in 1789, he begged earnestly to be allowed to return ‘home’ to Medford, declaring he was “ever a good friend of the Province”, and expressing the wish to marry again in his own country, “where, having already had one good wife, he was in hopes to get another, and in some degree repair his loss.” His prayer was, however, refused, and he died of smallpox in England in October 1781. By his will, Harvard College was given a tract of land in Worcester County, for the foundation of a professorship, which still bears his name. But, what is the connection between these two famous names from American history and Froyle?